All About Rococo

The Rococo Age: Whimsy, Grace, and the Art of Delight

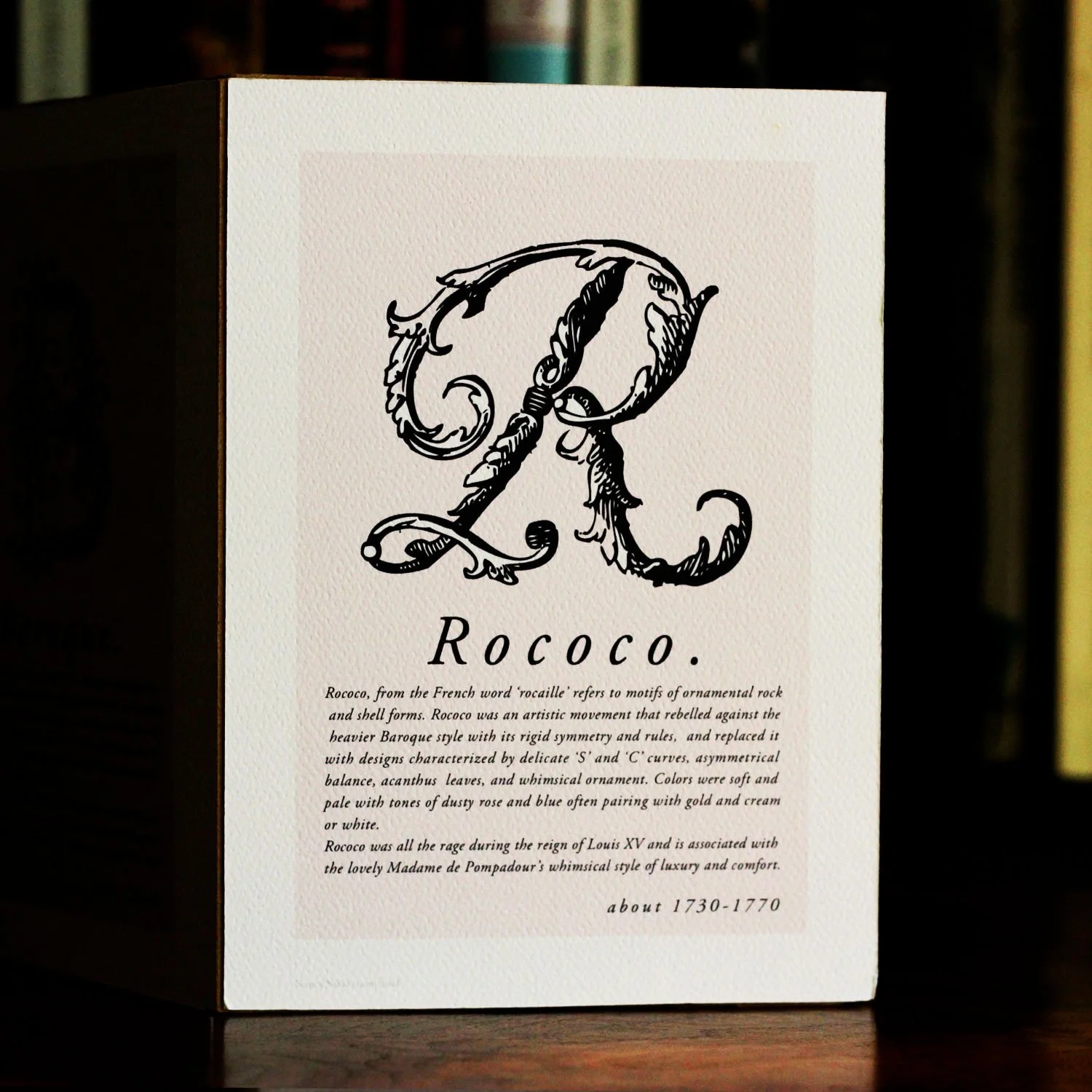

“Rococo, from the French word Rocaille, refers to rock and shell forms, and was an artistic movement that rebelled against the earlier and heavier Baroque style.”

Sèvres boat vase in whimsical styling with romantic cherub scenery. Also known as a pot-pourri à vaisseau. This was made for Madame de Pompadour in the color that would come to be known as Pompadour Pink.

If the Baroque period was the grand theatre of European art, then the Rococo era was its lighthearted afterparty — a world of pastel elegance, curling ornament, and intimate charm. Emerging in early 18th-century France, around 1715–1775, Rococo design reflected a cultural shift from royal ceremony to private pleasure, from Versailles’ majesty to the salons and boudoirs of Paris.

Origins and Essence

The word Rococo is derived from rocaille, referring to shell and rock ornamentation popular in French garden grottoes. This shell motif became a defining element of the style, symbolizing both nature’s playful irregularity and refined craftsmanship. After the death of Louis XIV in 1715, the heavy, moral grandeur of Baroque art gave way to a new spirit of intimacy and wit under Louis XV. The nobility, freed from the rigid etiquette of Versailles, decorated their Parisian townhouses with light, curvilinear designs celebrating romance, flirtation, and the pleasures of everyday life.

Interior rending by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier

Architecture and Interior Design

Rococo interiors abandoned Baroque symmetry for asymmetrical flow and organic movement. Walls dissolved into a continuous tapestry of plaster ornament — shells, garlands, scrolls, vines, and cherubs — often gilded and set against delicate hues of cream, pink, sky blue, and mint green. Mirrors multiplied light and illusion; painted panels featured pastoral scenes or mythological idylls.

Famed architects such as Germain Boffrand and Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier defined the French Rococo interior, most notably in the Salon de la Princesse at the Hôtel de Soubise in Paris (c. 1737–1740), where gilded stucco and mirrors create a dreamlike, fluid space.

French rococo armchair with typical soft coloring, luxury textiles and gilding.

Furniture and Decorative Arts

Rococo furniture was lighter, more feminine, and infinitely more comfortable than its Baroque predecessors. The cabriole leg, scrolling arms, and marquetry of exotic woods became signatures of the period. Ébénistes (master cabinetmakers) such as Jean-François Oeben, Charles Cressent, and Jean-Henri Riesener crafted pieces for royal patrons and Parisian salons alike.

Delicate Sèvres porcelain, Boulle marquetry, and intricate bronze ormolu mounts completed the tableau of luxury. Even small accessories—snuffboxes, clocks, and fans—embodied the Rococo fascination with artistry in miniature.

The Progress of Love: Love Letters, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, 1771-72

Painting

In painting, Rococo found its most lyrical expression. Artists such as Jean-Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, and Jean-Honoré Fragonard painted scenes of love, leisure, and theatre, often set in dreamlike gardens or gilded salons.

Watteau’s Pilgrimage to Cythera (1717) set the tone for an age intoxicated by beauty and grace; Fragonard’s The Swing (1767) remains the quintessential image of Rococo playfulness — silken, flirtatious, and bathed in dappled light. However, the paintings included in The Progress of Love series at the Frick Museum, remain my favorite.

Color and Mood

Rococo color palettes were delicate and sensual — pale pinks, celadon greens, creamy whites, blues like robin’s egg and forget-me-not, accented by glimmers of gold. The intent was to soothe the eye and elevate the spirit. In textiles and wallpapers, floral motifs reigned supreme: roses, ribbons, and festoons dancing in endless repetition.

Rococo cartouche for a book of ornamental prints by the German engraver, Johann Georg Pintz in the 1750s.

The Rococo Beyond France

From France, Rococo spread across Europe: to Bavaria and Austria, where architects like François de Cuvilliés created churches shimmering with gilded stucco and pastel frescoes (as at the Amalienburg Pavilion, Munich); to Italy, where Venetian painters like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo brought the style to celestial heights; and to England, where the lighter “Chippendale” furniture and plasterwork of Robert Adam reflected a tempered Rococo elegance.

The Decline and Legacy

By the 1770s, tastes shifted toward the sober lines of Neoclassicism, inspired by archaeological discoveries at Herculaneum and Pompeii. Yet Rococo’s influence endured in the language of interior design — in our love for curved lines, pale palettes, and intimate domestic spaces. Today, its essence lives on wherever beauty and craftsmanship are married with a touch of whimsy.

In essence, the Rococo was more than a style — it was a mood: an age of grace and laughter after centuries of grandeur. It invites us to remember that art need not always be solemn; it can be light, joyful, and delightfully human.